No Childhood in Mangroves: Climate Change Toll on Sundarbans Youth

A woman walks along the riverbank carrying a heavy load of firewood on her head, reflecting the daily labor and resourcefulness required for survival in this remote deltaic region (Photo - Raima Kayal, 101Reporters.

South 24 Paraganas: “When a man is in the forest, his wife behaves like a widow.”

“It’s the jongoler niyam,” says Manisha, barely 17, her voice almost lost in the humid stillness of a Sundarbans afternoon in West Bengal.

These “rules of the jungle” aren’t written down, but everyone who survives off the forest in these deltaic islands follows them with quiet devotion. When a man goes into the jungle, his household must respect certain rituals to ensure his safe return. No one cooks or eats meat. Women don’t wash their hair or wear sindoor. Strangers aren’t allowed inside the home. The wife lives as if widowed already: avoiding joy, colour, or company.

“You’re the first outsider I’ve allowed inside my house since my husband went into the jungle,” Manisha adds.

The room she invites the reporter into is modest, dim, yet spotless. A garland of marigolds withers in the shrine to Bonbibi — the forest goddess believed to protect those who dare to fish, gather crab, or collect honey in the tiger-haunted mangroves of the Sundarbans.

Manisha’s husband has gone fishing for five days now. He had ventured deep into the Sundarbans to fish — illegally. That means he crossed into the core zone of the Sundarban Tiger Reserve, a strictly protected area where no human activity is allowed. By law, fishing is only permitted in the buffer zone. But the legal waters offer little these days. With dwindling stocks and no other way to feed their families, many, like Manisha’s husband, take the risk. They gamble with their lives in forbidden territory, fully aware they may not return.

“No one goes there unless they’re desperate,” she says. “But that’s all we know now, desperation.”

She was 16 when she eloped, hoping to escape the constant anxiety of watching her mother wait for her father’s return from the jungle. “I thought marriage would set me free,” she says. “But now I wait too. I fast. I don’t wear sindoor. I pray. And I prepare myself, just in case he never comes back.”

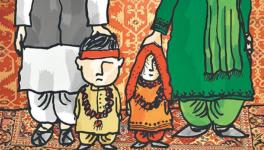

Young girl carrying puja materials for sale (Photo - Biswanath Maiti)

No time for childhood

The Sundarbans mangrove forest, one of the largest such forests in the world, lies on the delta of the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers on the Bay of Bengal. The region is intersected by a complex network of tidal waterways, mudflats—which are formed when silt and mud are brought in by the river water—and islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests.

In this region, childhood ends early. Before they turn 18, many girls elope or are married off, driven by poverty, fear and social pressure. Boys, meanwhile, take on the burden of earning a living, often before they finish school.

Take, for example, Subhasish Biswas (19) who has been working at a construction site in Andhra Pradesh for the past three years. “I dropped out after Class 9. Not because I wanted to, but because I had to,” he says.

His father and grandfather have spent their lives “working” in the jungle. “They’ve been attacked by tigers more than once. Still, they sometimes go back to the forest to fish,” Biswas says.

But fishing alone barely brings in Rs 70,000 a year for the family. Over time, they’ve had to mortgage land and gold just to survive.

“I had to start working so we could earn something,” he said. On a good work season, he makes up to Rs 20,000, sending home around Rs 12,000 to Rs 15,000.

It’s not easy, but for Biswas, migrating for work was the only option, the other alternative was going into the forest, which he was determined to avoid.

“If we had proper skill training: electrical work, plumbing, even something like solar panel installation I would never leave,” he says.

Fragile economy

To understand why childhood disappears so quickly in the Sundarbans, one has to understand the fragile economy of the region, deeply tied to natural resources: fishing, forest gathering, and seasonal migration.

Bibek Sardar (41), a third-generation fisherman, recalls a time when he could “catch Bhetki, Parshe, Java, and Bhola mach right at the riverbanks effortlessly.”

“But now we have to venture deep into narrow creeks to find them somehow.”

The key drivers of this decline in fish availability are environmental degradation and changes in river hydrology, according to The Sundarbans Fishers: Coping in an Overly Stressed Mangrove Estuary.

Researcher and author of the report Santanu Chacraverti explains that layers of sediment deposition are building up in the rivers as there’s no freshwater flowing in and the tides keep stirring things up. These not only block traditional fishing zones but also force fisherfolk into deeper, riskier waters.

“There isn’t just enough fish anymore. Many families still rely on fishing, even if not full-time. Look at Matla River — no freshwater flows in to dilute the saline water because the small tributaries have dried up. Now, it just swells with the tides. That’s why salinity keeps rising.”

And the rising salt levels in the water are upsetting the balance of the ecosystem.

“The main reason is farm runoff—when rain or cyclones wash pesticide-filled soil into the rivers,” he explains. “Tourism adds to the problem too, with boat fuel and plastic waste. But deep inside the forest, the water is still cleaner, and the fish are healthier.”

This pushes the locals to enter the protected core forest zones. These areas are richer in fish, but they are also the hunting grounds of the Royal Bengal Tiger.

A 2014 study by Dr Chandan Surabhi Das found a seasonal spike in tiger attacks in April, a time when salinity peaks in the estuarine waters.

A 2012 study by Mahadevia Ghimire and Mayank Vikas explains how climate change has reduced the amount of plant and fruit life in the forests and led to the submersion of forest land.

As a result, food has become scarce for animals and with fewer prey in the forest, the Royal Bengal Tigers are now straying more often into nearby villages in search of food, bringing them into direct conflict with people. The issue has been flagged in the West Bengal State Action Plan on Climate Change as well.

Sardar, too, says that tiger movement has increased noticeably in forested islands where tigers were once rare. “In places like Gazi, Sudhanyakhali, Lebukhali, Jhulobabni, Tara and others, the tiger attacks have increased in recent times,” he says.

According to experts, changes in forest management have also played a role in how people and wildlife are now sharing the space.

A man repairs his fishing net beneath a thatched shelter, a quiet moment of routine (Photo - Raima Kayal, 101Reporters).

Forests reshaped

According to Professor Tuhin Ghosh, Director at the School of Oceanographic Studies, Jadavpur University, after the government banned timber cutting to protect the forest, the plants and bushes grew violently. “The underbrush has become so big that tigers get their claws stuck and can’t chase prey like they used to. With less food in the forest, they’re crossing paths with humans more often, especially those who venture deep inside for fishing or honey collection.”

Human activities are amplifying climate vulnerabilities,” Ghosh added. “But if we focus on smarter water management and community resilience, we can reduce risks.”

Yet the scale of the crisis often goes unacknowledged. Official data on human-tiger conflict doesn’t reflect the true picture. The Sundarban Tiger Reserve claimed zero conflict cases in its 2023–24 report, a figure villagers dispute. By official definition, a “conflict” is only counted when a tiger enters a village. If a villager is attacked inside the forest, often while fishing or foraging without permits, it doesn’t get logged.

These uncounted deaths may not exist on paper, but they are painfully real for the families left behind. And it is often children who carry the weight of this unseen burden.

The cost paid by children

Sukumar Paira, former headmaster at Bijoynagar Adarsha Vidyamandir Hi and founder of a local NGO working with women and children in the Sundarbans, has watched this crisis unfold for decades. “These children, they smile, they play, but you can see the burden in their eyes,” he says. “Their fathers go off to dangerous forests or distant cities just to earn not more than Rs 10,000 a month. Their mothers carry both grief and responsibility. And the children? They grow up quietly, quickly and painfully.”

He remembers students who couldn’t afford textbooks because their fathers hadn’t come back from the forest. “Some would say, ‘Sir, Baba hasn’t returned, so we can’t buy the book yet.’ That kind of sentence stays with you forever.”

It’s the same for Asima Mondal (16) from Bali Island.

Her father fishes in the forest for weeks at a time. “During those days, we lose all contact. My mother stays strong, but I can feel the weight she carries. It’s like we’re all holding our breath until he returns.” If he brings back enough money, Asima can pay her tutors. If not, she falls behind. “I’ve just appeared for my Class 10 board exams. I want to study Bio Science, but there is no science stream in any school on our island. I’ll have to move to Kolkata. But how will we afford that when my father’s life itself is so fragile?” She doesn’t use social media. She barely goes out. “I just want a chance—to study, to grow, to live a life where my father doesn’t have to fight tigers for my tuition.”

Some distance away, Apratim (16) still relives the day his father was mauled by a tiger. It was during morakotal, the low tide that makes forest fishing easier. His father survived, but Apratim says, “We didn’t.”

The family had to seek treatment at a private hospital and they had to sell off their land and gold to pay the bills. Apratim’s father has undergone multiple surgeries already, but one more, costing Rs 2.5 lakh, still remains. The family wants to shift him to a government hospital for the final operation, but doctors there have refused to take the case, Apratim explains. It’s too sensitive, they say and must be handled by the same neurosurgeon who performed the earlier procedures.

Treatment after a tiger attack at government hospitals is usually not expensive. But timing is critical. Delays—either due to fear of alerting authorities or because of weak transport infrastructure—can make the difference between life and death. Though speedboats are available in some areas to rush victims to care, they are not always accessible. If patients are forced into private care, a single operation can cost lakhs, as they typically require multiple complex procedures.

Hospital bills have swallowed many parcels of land in the villages of Sunderbans.

“The incident also left my mother with anxiety attacks,” Apratim adds. “She gets palpitations whenever I even mention going to work. She thinks she’ll lose me too.”

Apratim has vowed never to enter the forest. He wants to join a vocational course instead.

Alternative livelihoods—like natural dyeing, pickle-making, and craftwork—exist in the area but remain small, outdated and hard to scale. “We don’t just need traditional skills,” says Professor Ghosh. “We need training in solar tech, electrical repair, and IT. These can offer sustainable options for youth.”

Raima Kayal is a freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.