José Mujica, Guerrilla Fighter Who Became Uruguay's President

Former Uruguayan President José Pepe Mujica. Photo: Presidencia de Colombia

Early life

José “Pepe” Alberto Mujica Cordano was born in Montevideo on May 20, 1935. His Uruguayan ancestry preceded the historical European migration to the Rio de la Plata at the beginning of the 20th century. His paternal family descended from Basques who arrived in Uruguay in the 19th century, while his mother was a descendant of Italians from the north.

Mujica studied in public schools, but did not manage to finish high school or go to university. Soon, his life was seduced by political militancy. At an early age, he joined the National Party, a center-right Uruguayan party, where he became Secretary of Youth, demonstrating political aptitude. However, the more reactionary positions within the party, in addition to the enormous effect produced by the Cuban Revolution of 1959, caused Mujica to break away from the National Party in 1962 and found the Popular Union, a socialist party.

The armed struggle

A few years later, the influence of the armed struggle waged by the left across the continent pushed Mujica to join the National Liberation Movement – Tupamaros. The group was an urban guerrilla movement that sought to unleash a national revolution, and he took an active part in its operations. Once the police registered him as a guerrilla, he went underground and abandoned his work in the countryside.

The Pacheco Areco government stepped up repression against leftist groups, and this intensified the work of the Tupamaros. In a skirmish with the forces of law and order, Mujica was shot six times. After several guerrilla operations, Pepe Mujica was arrested on four occasions, two of which resulted in escapes that became famous not only in Uruguay but throughout the continent for their preparation, ingenuity, and organization.

A solitary confinement of 13 years

Despite this, he was imprisoned again and spent 13 more years in prison (between 1972 and 1985), where he had to endure the conditions that prisons had in store for Latin American revolutionaries, such as torture and other abuses. The National Government declared him as a “hostage” and threatened the guerrilla movements that if they resumed their actions, their leaders would be executed.

Years later, looking back on that period, in which he spent most of his time in isolation, he said: “Those years of solitude were probably the ones that taught me the most…I had to rethink everything and learn to look inward at times, to avoid going crazy… When I was a prisoner, I spent almost 7 years without books, in a room smaller than this one. They moved me from barracks to barracks. Then I ended up contracting the vice of misanthropy, of talking to myself. That was like self-defense, in the conditions I was in, so that I wouldn’t lose my mind. But it became ingrained in me. It became a habit.”

Liberation and the Broad Front

The return to democracy implied the liberation of several political prisoners, among them Mujica, who returned to freedom in 1985. After attempting a revolutionary struggle, José Mujica opted to take a path framed within formal democracy, and under a new political movement called the Movement of Popular Participation (MPP), he joined the Broad Front, a broad alliance of left, center-left, and even center-right parties that contested several elections. Mujica himself was elected deputy in 1994 and was appointed in 1999 as President of the Senate, demonstrating a special connection with the Uruguayan population, who saw him as a coherent politician far removed from any kind of corruption.

In 2005, the Broad Front won the presidency of the republic under Tabaré Vázquez, who decided that Mujica, who by then was one of the most important leaders of the Broad Front, would be Secretary of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries. It was during this period that his ability to communicate in a clear, simple, and at the same time, a profound way, gained importance in Uruguayan politics. Mujica became an enormously charismatic character.

The humble president of Uruguay

These and other political qualities, such as showing himself as a unifying and mediating subject in the Broad Front and between governments such as the Uruguayan and the Argentine, paved his way as a presidential candidate. After the first electoral round, Mujica defeated Luis Alberto Lacalle on November 22, 2009, with about 52% of the valid votes. He was sworn in on March 1, 2010, as President of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay in a public square, together with his supporters, according to his wishes.

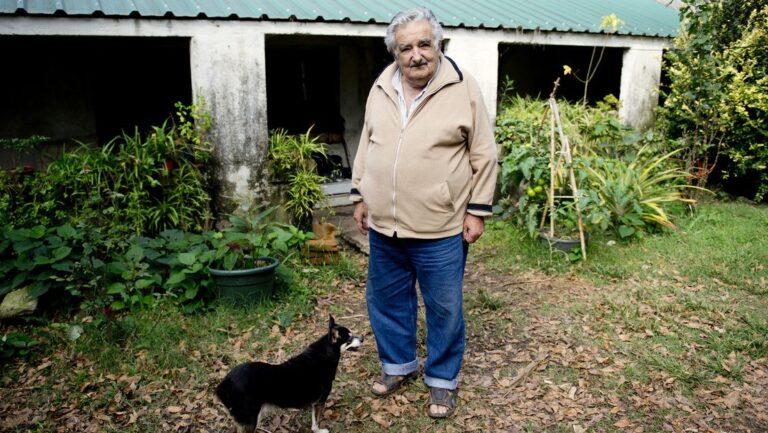

Soon, images of the life of Mujica and his wife, the important Uruguayan politician Lucia Topolansky, spread around the world. They rejected the luxuries offered by the presidential office. They continued to live in a humble house in the countryside with their animals, while driving an aging Volkswagen to get to their place of work, the office of the President of the Republic. Many journalists and filmmakers became interested in his story and his humility, so they started to conduct interviews and documentaries about the so-called “poorest president in the world”.

Pepe Mujica at his home in Uruguay.

However, Mujica always refused to be called poor, because he considered that poverty consisted of something different: “What is it that attracts the world’s attention? That I live with little, in a simple house, that I drive around in a little old car, are those the novelties? So, this world is crazy because it is surprised by the normal. The poor are those who want more, those who can’t afford anything. Those are poor because they get into an endless race. And as I was president, they came here and saw this little house, and they admired me. But they don’t emulate my life!”

His government was characterized by an increase in public spending and a decrease in poverty, which went from 13% to 7%, while increasing the minimum wage by 250%. In terms of social work, his government was characterized by offering housing to families who did not have a home. To obtain funds, Mujica himself donated 87% of his salary to a fund that was also fed by the solidarity contributions of several companies, as well as thanks to the sale of State properties.

Regarding the expansion of rights, he supported the expansion of reproductive rights, marriage as a civil union between people regardless of their sex. His proposal to legalize the consumption of marijuana for recreational purposes was controversial. Mujica argued that this measure sought to eliminate the power of drug trafficking: “What scares me is drug trafficking, not drugs. And by repressive means, it is a lost war: it is being lost everywhere.”

He was also one of the main promoters of the Uruguayan state’s recognition of the persecution, torture, and murder of dozens of left-wing party militants during the 20th century, especially during the military dictatorship (1973-1985). Thus, he promoted and strengthened the policy of recovery of historical memory, which today has become an important public policy of the State.

Final years

Once his term as president ended, Mujica was elected senator during the 2015-2020 and 2020-2025 terms, although in 2020 he resigned from office due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite speculation of a possible return to Executive politics as Secretary of Agriculture and Livestock, he rejected such a possibility.

In 2024, he announced that he was suffering from esophageal cancer, and in 2025, he reported that the malignant cells had spread to other parts of the body, so he was simply “waiting for the inevitable”. Despite this, he played an important role in the last presidential election, in which the Broad Front reconquered the government with Yamandú Orsi after the right-wing government of Lacalle Pou. Mujica, thanks to his great popularity, participated in several rallies in which he called for support for Orsi and for the Broad Front to return to the executive.

On May 13, Mujica died from cancer, leaving his supporters without one of the most important references that the Broad Front had during its history. Indeed, Mujica became the most emblematic national and international image of the unity of the Uruguayan anti-neoliberal political parties. His short and incisive phrases are still remembered as examples of Socratic wisdom that seem to come out of ancient history books, but that express the enormous impact of his political coherence and sensitivity.

In a political rally, in front of Broad Front militants, he said: “I am an old man who is very close to undertaking the retreat from which there is no return. But I am happy because you are there, because when my arms leave, there will be thousands of arms replacing me.”

Thus, Mujica will remain a symbol and a legend in Uruguayan history; a sort of example that, as he stated, few were willing to follow. In this sense, Mujica expressed in his words an ironic satisfaction before life and an incredulity before a world that seems to become more complex, even though, as the ex-guerrilla himself stated, perhaps what we need is to stop and look at ourselves deeply: “You are going to grow old and you are going to have wrinkles, and one day you are going to look in the mirror and you will have to ask yourself, on that day, if you betrayed the child you had inside you.”

Courtesy: Peoples Dispatch

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.