How Weak Policies Failed Millet, Favoured Wheat - 3

Sehore Mandi in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh, is a major agricultural market where farmers sell a variety of crops, including wheat, soybean, and pulses. Image: Madiha Khanam

Millet takes longer to grow, has lower yields, and carries higher risks, making it an unappealing choice for farmers seeking economic stability. But it is a very appealing choice for agricultural policy experts trying to chart a course to a resilient agricultural policy for India. Yet, as water shortages worsen and climate pressures mount, policy failures are closing off one of the only viable paths for India to achieve a viable agricultural future.

Part 1 of this investigation unpacks how wheat’s dominance over millet makes economic sense. Part 2 explores the environmental perils of wheat cultivation. In Part 3, we examine why millets remain ‘ghaate ka sauda’ —a business of loss. Major failings of the government programme to increase millet adoption include weak procurement, inconsistent incentives, and, most importantly, a lack of real financial backing.

Government subsidies on inputs and investment in research help costly wheat, hurt more efficient jowar

When asked about potential solutions to encourage farmers in India to grow jowar or other millets, Rishiraj Purohit, Programme Manager (Sustainable Agriculture) at Samarthan NGO, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, observed, “The government’s efforts to promote millets do not appear very impactful. Most initiatives seem confined to verbal promotion. While there might be some support for Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in value addition, the large-scale launch needed to truly boost millet cultivation is still absent. For instance, initiatives like the Sri Anna programme and Millet Year 2023 have succeeded in raising awareness, but awareness alone isn’t sufficient to drive meaningful change.”

The government’s marketing efforts have failed to salvage the reputation of the healthiest grains in India and have been undermined by their continued support of water thirsty crops, such as wheat. While jowar and bajra were referred to as ‘gareeb ka dhaan’ (poor man’s grain), it was branded in a way that linked it to tribal or lower-income communities. Eating jowar and bajra became associated with lower social status. In contrast, wheat became a symbol of affluence—if you were eating wheat, you were considered to be from a better-off family.

Meanwhile, subsidies on water and electricity made wheat the more lucrative choice for farmers. Babu Lal, a 45-year-old farmer from Rasooliya Pathar, Bhopal district, shared, "Even though we still receive electricity bills, the government provides subsidies that make it more affordable for small farmers like us to grow wheat." These subsidies, while offering immediate financial relief, inadvertently encourage the overuse of groundwater resources for wheat cultivation, intensifying the strain on already depleting water tables.

A farmer sharing his views on the dynamics of wheat and jowar cultivation in his village. Image: Madiha Khanam

Today, only hybrid jowar is available; the traditional, desi jowar is no longer grown. The perception still persists that jowar is a grain for the poor and tribal communities. However, the elite class has now realised that jowar can help in controlling blood sugar levels in diabetes.

Despite its minimal production costs, jowar procurement and yield remain low. Growing jowar is much cheaper compared with wheat, as it does not require irrigation and relies on rain. Farmers sow it during the rainy season in June, and within four months, it starts bearing fruit, with harvest taking place in January or February. In contrast, wheat has higher production costs due to expenses for seeds, manure, medicine, and water.

Jowar: Higher MSP Can’t Offset Low Demand

The Minimum Support Price (MSP) is a critical tool in India's agricultural system, designed to protect farmers from price fluctuations in the market. It ensures that farmers receive a guaranteed price for their crops, helping stabilise their income and prevent distress sales. But sometimes, it just does not work as intended. The MSP for jowar is now higher than that for wheat, offering farmers a better price for their jowar harvest. Despite this, wheat continues to dominate at the national level.

Siraj Hussain, former Union Agriculture Secretary, in a telephonic interview, emphasised that MSP was not a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, it should be part of a broader policy framework that integrates comprehensive farmer welfare and strategic support for sustainable agriculture. When implemented thoughtfully, MSP can serve as a crucial policy tool with significant potential.

Over the past decade, the MSP for jowar has more than doubled, increasing from ₹1,540 in 2014-15 to ₹3,203 in 2023-24. In contrast, wheat’s MSP has grown by about 1.6 times in the same period, from ₹1,450 to ₹2,275. Despite jowar’s higher MSP, the government largely does not procure it, leaving farmers with limited buyers and uncertain returns. Jowar’s selling price is quite good, ranging from Rs. 3,000 to 4,000 per quintal, but the issue lies in finding buyers.

The wheat supply chain is smooth and efficient, while the jowar supply chain is a mystery

If we connect all the dots with respect to the market economics, it becomes clear why millets like jowar are not receiving the support they need.

There have been numerous campaigns, rallies, and jagaran abhiyaan (awareness campaigns) urging people to "eat millets." Millets aren’t new to the public—our ancestors have been consuming them for generations. Instead of simply promoting their consumption, the government should focus on demonstrating the benefits of growing millets. Farmers need to know:

-

How much they can earn by growing millets.

-

Which varieties are best for cultivation in their region.

-

The expected yields and the resources needed.

Sehore Mandi in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh, is a major agricultural market where farmers sell a variety of crops, including wheat, soybean, and pulses. Image: Madiha Khanam

“There is a grading process for wheat that plays a significant role in its value chain. When wheat is harvested, it’s sent to the Food Corporation of India (FCI), which distributes it at Rs. 2 per kg to the poor. The surplus is then stored in godowns and it is then sold to companies.

The key point that this article wants to highlight is that wheat has a visible, end-to-end ecosystem. It’s clear how the by-products will be used throughout the entire cycle, ensuring that no part goes to waste.

Purohit explains how the value chain works for wheat. In contrast, jowar lacks a clear and transparent value chain, making its by-products less utilised.

He adds: “The entire challenge is tied to the market ecosystem and agroecology, which makes it difficult to integrate jowar into the mainstream food supply chain. However, a game-changer in the market could make a significant difference. For example, if there were a jowar variety with extraordinary yield, similar to that of maize, farmers would likely adopt it and start growing it. Currently, jowar's yield stands at around 10-15 quintals per acre, but birds consume roughly 5-7 quintals per acre, leaving little benefit for the farmers.”

Is Govt Procurement the Secret to Millet’s Future?

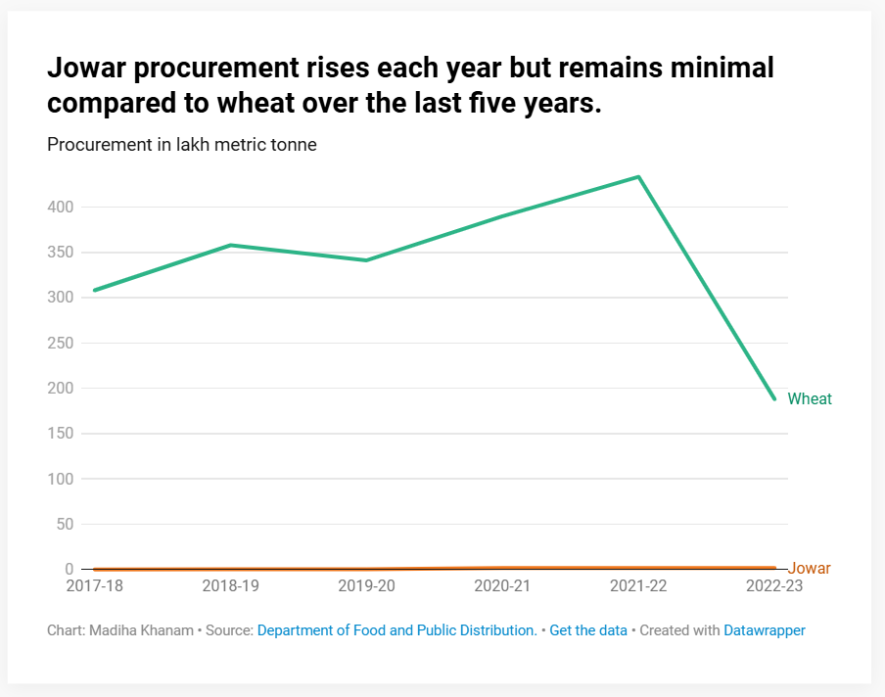

The government is increasing jowar procurement each year, but it remains very low compared to wheat over the last five years.

Procurement serves as a safety net for farmers, where the government buys crops at a fixed MSP to ensure income stability. However, wheat enjoys far greater procurement volumes and consistent government backing, making it the preferred crop for farmers despite its higher water demands. This disparity has left jowar struggling to compete in both production and profitability.

In the past five years, over one-fourth of wheat produced nationally has been procured, while jowar farmers have seen less than one-20th of their harvest procured.

Hussain emphasised the interconnectedness of MSP and procurement, stating: “The reality is that the government doesn’t back the MSP for jowar or millets with active procurement. Without government procurement, farmers are left uncertain about the price they’ll receive for jowar. In comparison, wheat farmers benefit from not just the MSP but also an additional bonus, along with guaranteed procurement. This assurance makes wheat cultivation a more secure choice for them. For jowar, there’s a lack of buyers. Consequently, the government’s support for jowar often feels like nothing more than lip service. For instance, the Year of Millets 2023 seems more symbolic than impactful, often coming across as lip service rather than a meaningful initiative.”

Binod, a 28-year-old farmer from Rasooliya Pathar, Bhopal district, said: “In every village in Madhya Pradesh, the government has opened chaupals or societies where you can sell wheat at the set price. It has been 7-8 years since the government established this society in all the villages to buy wheat from us. For one acre, the government society takes 18 quintals of wheat. We generally get 22-25 quintals of wheat per acre, so the remaining amount is sold at the Sehore mandi.”

The entire responsibility cannot be placed on farmers by simply saying, "Grow millets, grow millets." It won’t make much of a difference unless millets become 80-90% of the diet for the majority of the population. A structural shift needs to start with government procurement.

If the government buys millets and includes them in food distribution programmes for poor families instead of wheat, diets could gradually shift back to millets, starting with the poor instead of the rich and those who rely most on subsidised food. As Purohit emphasised, “even if you and I work on promoting millets just for the sake of it, it won’t lead to meaningful change.” Without structured support, millets remain a less attractive and less viable option for farmers in India.

(Concluded)

Madiha Khanam is an architect, urbanist, and researcher. Her work focuses on cities, urban regeneration, geoinformatics, agriculture, water, and environment.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Environmental Data Journalism Academy- a programme of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and Thibi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.