Bihar Elections 2025: Voters’ List Revision Sparks Fear of Disenfranchisement

Enumeration form being distributed in Kahalgaon assembly constituency of Bhagalpur district in Bihar

The Election Commission of India’s (ECI) Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls, launched on June 24, has ignited a fierce political and legal battle, with fears of widespread voter disenfranchisement looming large. The exercise, aimed at updating Bihar’s voter list ahead of the upcoming Assembly elections, has drawn sharp criticism for its documentation requirements, tight deadlines, and exclusion of widely held identity documents like Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards.

Bhagalpur, a historic city on the banks of the Ganges, is a microcosm of Bihar’s complex socio-political landscape. With its diverse population of urban traders, rural farmers, and migrant workers, the city reflects the state’s challenges of poverty, migration, and limited access to documentation.

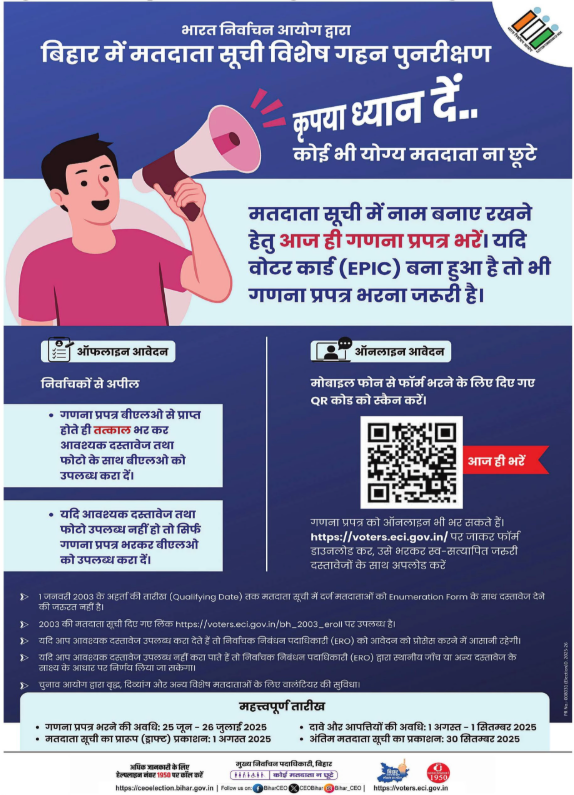

The ECI’s SIR requires all 7.9 crore voters in Bihar to submit enumeration forms, with 4.96 crore electors registered after January 1, 2003, needing to provide additional documents to prove their date and place of birth. For those born after 1987, proof of their parents’ identity is also mandatory, unless their parents were listed in the 2003 rolls.

The ECI has specified a list of 11 documents such as birth certificates, passports, and caste certificates, but notably excludes Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards, which are among the most accessible forms of identification for Bihar’s poor and marginalised communities.

The exclusion of these documents has sparked outrage, particularly among marginalised groups, including Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Muslims. In the city’s crowded slums and rural outskirts, many residents lack the documents required by the ECI.

“I have an Aadhaar card and a ration card, but no birth certificate,” said Rani Devi, a 45-year-old daily wage laborer in Bhagalpur’s Nathnagar area. “How am I supposed to prove I’m a citizen? I’ve voted in every election since I was 18. Now they’re saying I might lose my vote.” Rani’s story is not unique.

27-year-old Shivam Kumar, who has three brothers, says all four of them have voter ID cards. They all have voted in the last Lok Sabha elections. But, when it comes to attaching documents in SIR, he only has his 10th class marksheet. The rest three brothers don’t even have that as they didn’t go for higher schooling. They don’t have any of the 11 required documents either. This has put the family in a position of insecurity regarding their voting rights and citizenship.

With Bihar’s high poverty rates and significant out-migration, estimated at 1.76 crore people between 2003 and 2024, many residents, especially the poor and minorities, struggle to produce the required paperwork.

SIR Awareness Rath being flagged off by District Election Officer-cum-District Magistrate of Bhagalpur

In Kadwa Diyara, a flood-prone island on the Ganges in Bhagalpur, the SIR has left residents like Savita Devi, a 38-year-old widow, in a state of despair. Savita, who lives in a modest mud house with her three children, lost most of her possessions, including critical documents, during the devastating floods of 2023. “Whatever documents I possessed, they all were washed away when the river came into our home,” she recounted. “I managed to get a new Aadhaar, but the BLO says it’s not enough. I don’t have a birth certificate or any other papers they want.”

Rani and Savita have voted in the past general and assembly elections since they were eligible, but now fear being struck off the voter list.

The floods, a recurring menace in Kidwa Diara, have left many residents in similar predicaments, with no access to the documents required by the ECI. Savita’s attempts to navigate the ECI’s online portal have been futile, as the nearest cyber café is a boat ride away in Naugachia, and connectivity is unreliable.

The Apex Court Hearing

The Supreme Court’s hearing on July 10 offered a glimmer of hope. A bench comprising Justices Sudhanshu Dhulia and Joymalya Bagchi refused to stay the SIR but directed the ECI to consider including Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards as valid documents for voter verification. The court noted that the ECI’s list of 11 documents was “not exhaustive” and emphasized that excluding widely held documents like Aadhaar was problematic, especially given its use in other government processes like obtaining caste certificates.

The court also questioned the timing of the SIR, asking why it was being conducted so close to the elections and why it appeared to focus on citizenship verification, a responsibility typically under the Home Ministry’s purview. The ECI was directed to file a counter-affidavit by July 21, with the next hearing scheduled for July 28, before the draft voter list is published on August 1.

The Supreme Court’s intervention has been hailed by opposition leaders as a step toward inclusivity. Congress MP KC Venugopal called it a “relief for democracy,” expressing hope that the ECI would heed the court’s suggestion. RJD MP Manoj Jha echoed this sentiment, stating, “The Supreme Court has shown the path of inclusion amid people’s growing fear of exclusion.”

However, the court’s refusal to halt the SIR has left many anxious, as the July 26 deadline for submitting enumeration forms looms. The tight timeline, combined with the ECI’s requirement for documentary proof, has fueled fears that millions could lose voting rights, particularly in marginalised communities.

People Behind SIR: The BLOs of Bihar

In Bhagalpur, the SIR has placed immense pressure on Booth Level Officers (BLOs), the grassroots workers tasked with conducting door-to-door verification. With 77,895 BLOs along with 20,603 newly appointed BLOs and other election officials, over 4 lakh volunteers who are supporting the elderly, PwD, sick and vulnerable populations along with the 1.56 lakh proactive force of Booth Level Agents (BLAs) who have been appointed by all recognised political parties, the ECI is relying heavily on these officials to ensure the exercise’s success.

Till July 10, a total of 5,22,44,956 Enumeration Forms, which is 66.16% of the total of 7,89,69,844 (nearly 7.90 crore) existing electors in Bihar, have been collected. The electors still have 15 more days left to submit the form.

In Bhagalpur’s densely populated areas like Kahalgaon and Pirpainti, BLOs are struggling to cover thousands of households within the stipulated timeframe. “We’re working day and night, but it’s impossible to verify every voter properly in such a short time,” a BLO from Bhagalpur’s Barari village said. “Many people don’t have the documents, and some don’t even understand what we’re asking for. It takes time to make them understand why this process is being carried out and how they can submit the forms.”

The ECI’s communication strategy has added to the confusion. Front-page advertisements have been published in Patna newspapers, urging voters to submit forms even without the required documents, stating that Electoral Registration Officers (EROs) could verify eligibility through local investigation or other evidence. This move, seen as a response to opposition pressure, was met with skepticism.

Screengrab of ECI advertisement published in newspapers in Bihar

“The ad said we could submit forms without documents, but the BLO told me I need a birth certificate or I won’t be counted,” said Mohammad Asif, a shopkeeper in Bhagalpur’s Tilkamanjhi area. The discrepancy between the ECI’s public statements and the instructions given to BLOs has eroded trust in the process.

The SIR’s implications extend beyond Bhagalpur to districts like Katihar, where poor internet connectivity has compounded the challenges. The ECI has encouraged voters to download enumeration forms from its website and submit them online. However, in Katihar’s rural areas, unreliable internet access makes this nearly impossible.

“The ECI website doesn’t load properly here,” said Afreen Ansari, a college student in Katihar’s Manihari block. “Even when it does, the process is so complicated that most people give up.”

During this period of past 16 days since the beginning of the SIR exercise, 7.90 crore forms were printed and nearly 98% forms (7.71 crore) have already been distributed to the electors whose name were in the electoral roll as on July 24, as per the ECI. However, many people we spoke to, still said that they are yet to receive the enumeration forms.

In flood-prone areas like Katihar, where monsoon rains disrupt communication networks, the reliance on online submission is likely to exclude many rural voters, particularly those from marginalised communities.

The Politics over SIR

The political fallout from the SIR has been explosive. On July 9, Rahul Gandhi and Tejashwi Yadav led a massive protest march in Patna, joined by leaders from the INDIA bloc, including CPI(ML) Liberation’s Dipankar Bhattacharya, CPI’s D Raja, and Vikassheel Insaan Party’s Mukesh Sahani. The march, which aimed to reach the ECI’s office in Patna, was stopped near the Shaheed Smarak, with police deploying heavy forces to maintain order.

The Opposition called for a statewide “Bihar bandh” on the same day, disrupting road and rail traffic in districts like Araria, Purnia, Katihar, and Muzaffarpur. Protesters burned tires and blocked National Highway, accusing the ECI of attempting to suppress votes from marginalised groups. “SIR is not only an attempt to steal your vote but also your future,” Rahul Gandhi said, holding a copy of the Constitution during the protest. Tejashwi Yadav went further, alleging that the ECI was acting as an “arm of a political party” and questioning whether “two people from Gujarat”, an apparent reference to Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah, would decide Bihar’s voter eligibility.

The Opposition’s accusations are rooted in concerns that the SIR could disproportionately affect voters unlikely to support the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA). In Seemanchal region, which has a significant Muslim population, fears of exclusion are particularly acute. A clause in the SIR guidelines empowering EROs to refer “suspected foreign nationals” to authorities under the Citizenship Act, 1955, has raised alarms about potential targeting of minorities.

“This feels like a backdoor NRC,” said an activist from Patna, on the condition of anonymity. “Many Muslims in Bihar don’t have birth certificates or land records. If their names are removed, they will lose their voice.” The opposition has pointed to the ECI’s decision to exclude Aadhaar, which is widely used by minorities and the poor, as evidence of an exclusionary agenda.

Rahul Gandhi addresses supporters in Patna on the day of Bihar Bandh

The NDA, led by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has dismissed these claims as “absolutely false.” BJP’s Rajiv Pratap Rudy argued that the ECI’s mandate to revise electoral rolls is constitutional and necessary to remove non-citizens and duplicate entries. “The opposition is politicising a routine process,” said BJP leader Ravi Shankar Prasad.

The ECI has justified the SIR by citing rapid urbanization, migration, and the inclusion of ineligible voters since the last intensive revision in 2003. However, critics like members of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) argue that the exercise is unprecedented in its scale and timing, and that it is a de novo preparation of the electoral roll, effectively junking the existing one, which was updated as recently as January this year.

The ADR, along with other petitioners like Yogendra Yadav, Mahua Moitra, and Manoj Jha, had challenged the SIR in the Supreme Court, arguing that it violates fundamental rights under Articles 14, 19, 21 and 326. The petitions highlighted the risk of disenfranchising over 3 crore voters, particularly those from marginalised communities who lack the required documents. Senior advocates like Abhishek Manu Singhvi and Kapil Sibal have called the SIR a “citizenship screening” exercise, arguing that the burden of proof should lie with the ECI, not voters. “Disenfranchising even one eligible voter affects the level playing field and hits the basic structure of democracy,” Singhvi told the court.

In Bhagalpur, the fear of disenfranchisement is palpable. Migrant workers, who form a significant portion of the city’s population, are particularly vulnerable. Many have moved to cities like Delhi and Mumbai for work, making it difficult to return and submit forms by the deadline. “I’m in Mumbai working as a driver,” said Rajesh Paswan, a Bhagalpur native, over a phone call. “How can I come back to submit a form? And what documents? I only have my Aadhaar.”

BLOs distribute Enumeration forms to voters in Bhagalpur

The controversy has also drawn attention to the ECI’s inconsistent stance on Aadhaar. While the ECI has historically accepted Aadhaar for voter registration under Form 6, its exclusion from the SIR’s document list has baffled many. “For ten years, this country has gone crazy saying Aadhaar, Aadhaar, and now you won’t accept it for identification?” senior advocate Gopal Sankaranarayanan asked during the Supreme Court hearing.

The ECI’s counsel argued that Aadhaar is not proof of citizenship, a point reiterated by former CEC Ashok Lavasa. However, critics counter that the 11 accepted documents, like caste certificates and land records, are also not definitive proof of citizenship, making the exclusion of Aadhaar arbitrary.

As the July 26 deadline approaches, Bihar’s residents are racing against time. In rural areas, where literacy rates are low and access to documents is limited, the SIR has created an atmosphere of fear. “People are worried they’ll lose not just their vote but their rations and pensions too,” said Anil Kumar, a social worker in Bhagalpur’s Naugachia area. The opposition’s allegations of a broader conspiracy to strip marginalised groups of their rights have resonated with many, particularly in the wake of the Maharashtra elections, where similar concerns were raised.

The SIR’s outcome will have far-reaching implications for Bihar’s democratic process. With the Supreme Court set to revisit the issue on July 28, all eyes are on whether the ECI will adjust its guidelines to include Aadhaar, voter ID, and ration cards, as suggested.

For now, Bhagalpur and the rest of Bihar remain on edge, caught between the ECI’s push for a “clean” voter list and the very real risk of excluding millions from the democratic process. The battle over Bihar’s electoral rolls is a test of India’s commitment to inclusive democracy, and its resolution will shape the state’s political landscape for years to come.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Delhi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.